|

MEASURING INSTRUMENTS FOR SOLAR TIME AT MOUNT BEGO Vallée des Merveilles sector Dr. Jérôme MAGAIL |

|

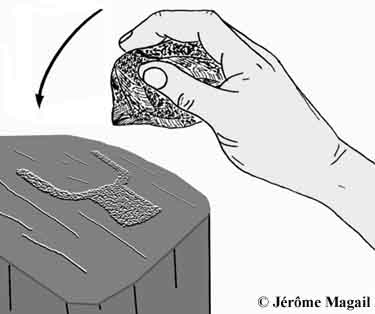

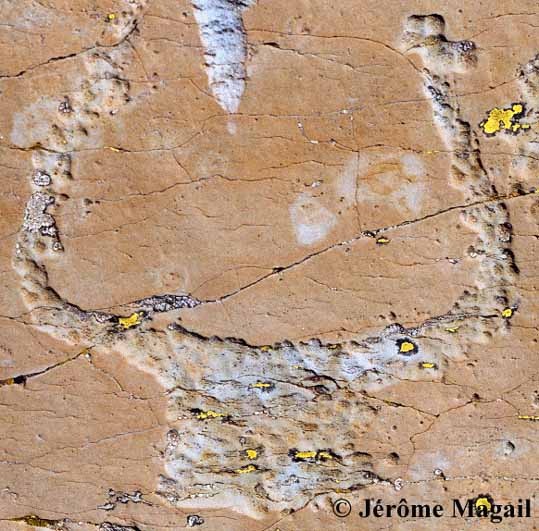

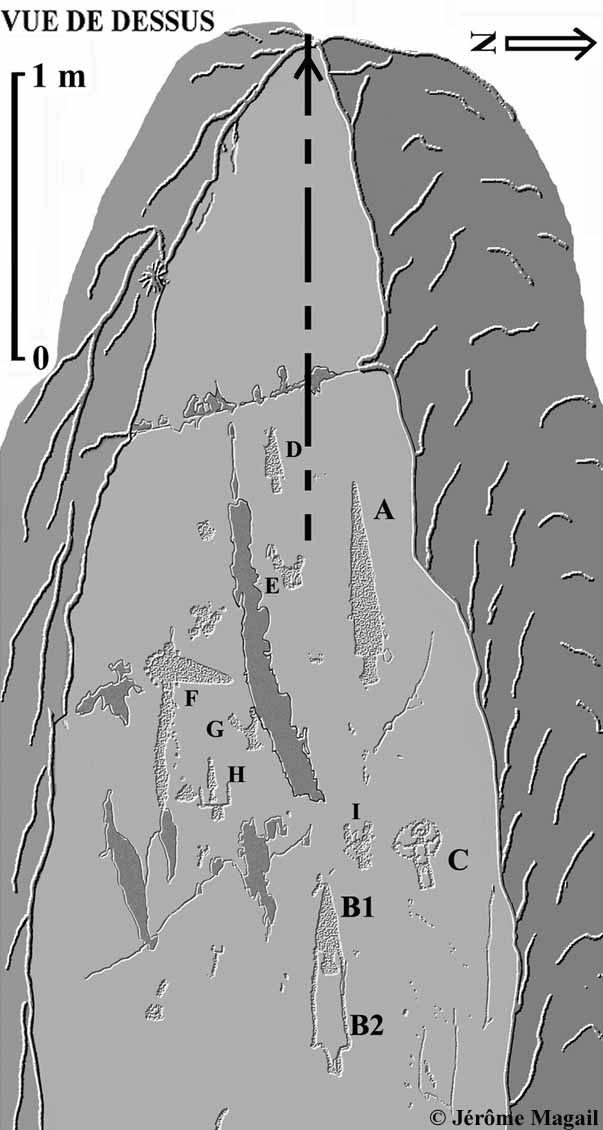

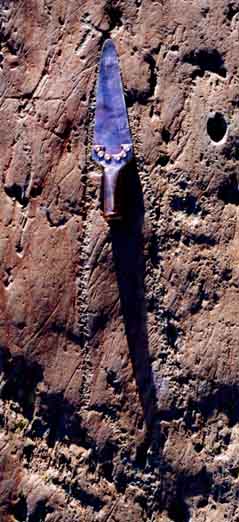

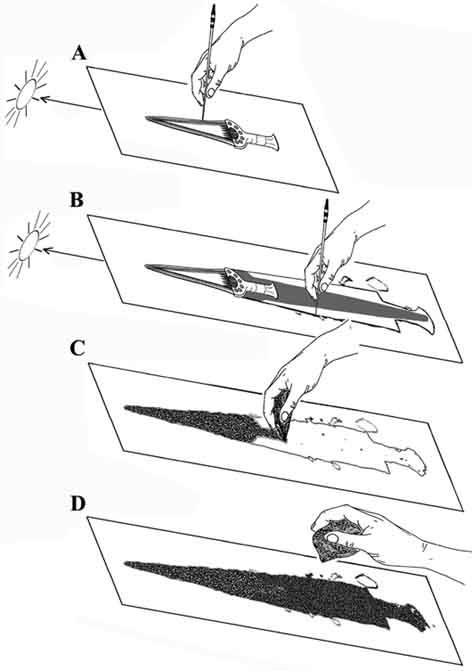

Around 2000 BC, over 37,000 engravings were carried out on the rocks of the Mount Bego region (fig. 1) in the Alpes-Maritimes in Southern France (Commune of Tende). The Bronze Age populations repeated the same figures each summer at between 2,000 and 2,600 meters above sea level. Nearly hall of these petroglyphs are rectangular forms with two horns above, schematic representations of bovines (fig. 2). Other iconographic themes are hundreds of daggers, halbards and geometric forms, including possible divisions into sections. Engraved harnesses (fig. 4) attest that there was already domestication of bovids and the sectional figures evoke the way in which these groups divided their territory. However, the original motivation of the authors of these thousands of engravings carried out by cast percussion (fig. 3) is still enigmatic. |

|

Fig. 2 : Bovine engraving. |

Observing the iconography suggests cult practice, without being able to establish its significance. Perhaps it is better to ask: "what were these engraved rocks used for?" rather than: "what do these engraved rocks mean?". A tentative reply has come several times from different researchers identifying solar divinities or a sun cult at Mt Bego. The European populations at the end of the Neolithic, whose agropastoral identity is certain, constructed monuments such as Stonehenge in England, oriented towards the rising sun at the solstice. |

|

Fig. 4 : Engraving of two yoked bovines pulling a plough. |

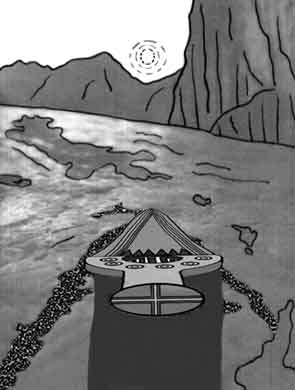

Are certain engraved rocks at Mount Bego oriented towards the sun to pick out certain dates? After a survey and some ton years of study it would seem that four rocks are measuring instruments for solar time (J. Magail 2001). Two engraved rocks in particular were used as seasonal solar sundials. Sun sights were carried out in order to identify the spot where the star would pass a year later. The use of gnomons with the direction of the shadow showing annual dates is also certain. Thus, the engravings on the slab called "The Dancer" are directed towards the setting sun of the 8th of September (fig. 5). The engravers inscribed overlong arms (fig. 6, A & 8) so that the shadow of a real dagger, placed at the edge of the engraving arrives at the level of a handle engraved only that day (fig. 7). This clever method of identifying a seasonal date shows the accuracy of the calendar that these pastoralists were able to establish. They only had to count the number of days between two measures carried out on this slab to know that the year had 365 days. |

|

Fig. 5 : Sketch of the orientation of the slab called "The Dancer" towards sunset. |

Fig. 6 : Sketch of all the engravings on the slab called "The Dancer". |

|

The method was to choose a slab whose surface was oriented towards the horizon and to target the setting sun with the aid of a dagger placed on the rock. At the planned date, the engravers waited for the moment that the sun was going to disappear behind the mountains to fix it with the blade of their weapon. Given that the sunset moves around the horizon from day to day, the star passes the engraved mark on only one evening in summer. To fix the direction shown by the real dagger, its contour and shadow were drawn with the aid of a pin or a flint, then the rock was more deeply marked by means of cast percussion (fig. 8). Four thousand years later, the cupulae that were aligned on a line can still be seen on the edge of engravings. In the summers following the engraving of these weapons, men placed their daggers on the rock and waited for the evening when their shadow was in the long axis of the engraving (fig. 9). When the observation was correct, the awaited date had arrived. In these hostile spots, the shepherds of the Copper Age could not stay at Mount Bego later than mid-September as the cold could suddenly arrive and decimate their flocks. |

|

|

|

|

| Fig. 7, 8 & 9 : Reconstruction of a bronze dagger positioned on the evening of 8 September alongside engravings A, B & D. | Fig. 10 : Method and inscribing technique of the engravings of the large daggers. |

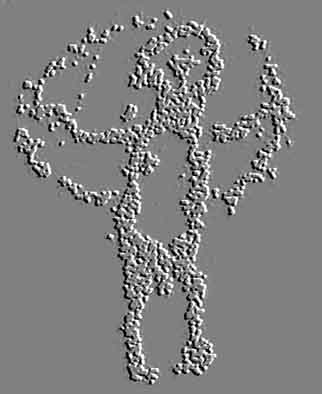

Fig. 11 : Anthropomorph of the slab called "the Dancer". |

The engravings on the slab was not just a profane temporal measurement. The choice of a bronze dagger as gnomon, made of a luminous precious metal extracted from the earth, seems to have had a sacred significance. The anthropomorphic figure engraved alongside the daggers, encircled by an ellipse, also recalls the cosmology of its maker (fig. 6, C & fig. 10). The analysis of three distinct researchers, Roland Dufrenne, Henry de Lumley and Emilia Masson, who have interpreted this figure as a personage linked to a solar cult, corroborates the discovery of the orientation of the daggers. |

|

|

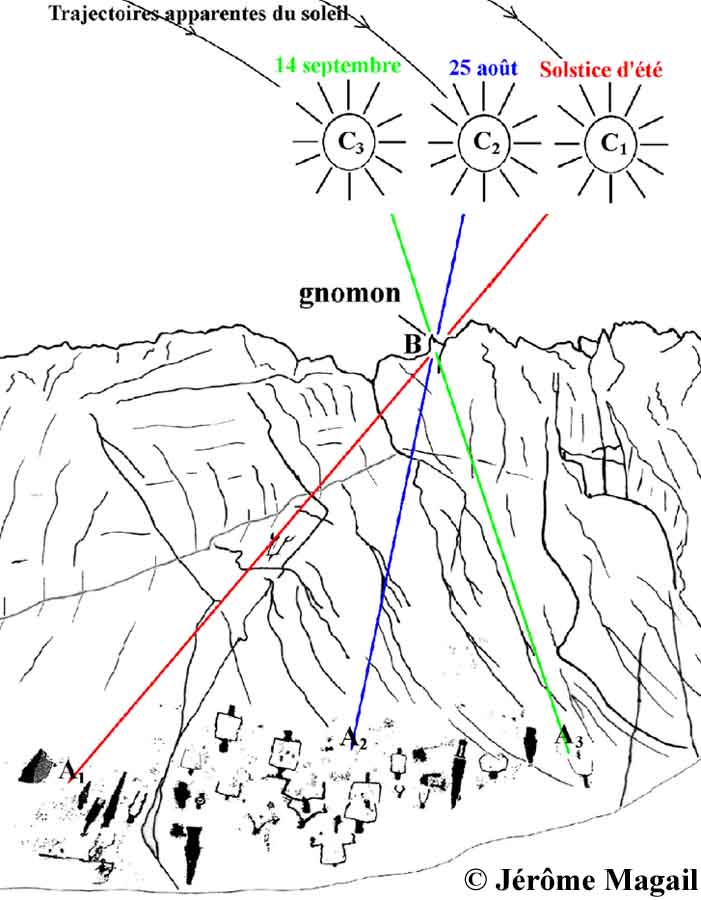

On another rock, a series of petroglyphs are indicated in the evening by the shadow of a groove made in the rock. After examination, it would seem that this series corresponds to the period running from the summer solstice to the 14th of September, the shepherds' season. The 7,000 engraved rocks, with a very small number serving as sundials, were linked to ritual behaviour, very probably based on religious dates. |

Fig. 13 : Vallée des Merveilles sundial. |

Fig. 14 : Sketch of sundial. |

|

The dates indicated by the instruments of temporal measurement could have indicated not only the

best moment for various agropastoral activities but also liturgical moments. Also, a large number of the other petroglyphs

could have Il inscribed on dates dictated by the sundials. Divinities could have been invoked thanks to ritual inscriptions,

in order to ask for a prosperous year or in thanks for successful preceding seasons. The exceptional repetition of thousands

of schematic bovine figures suggests an annual cult at a precise period. Other Mount Bego petroglyphs probably had an archaic

ideographic function founded on an association of figures (fig. 11).

If numerous techniques of flint knapping and material making have long been studied, little research has been carried out

on prehistoric time measurement techniques. Time measurement is necessary to labour, sow, harvest and carry out transhumance

at the right moment. The methods used at Mount Bego are very close to the practices involving gnomons of agropastoralists

observing the apparent movements of the sun in their daily variations. The Bronze Age people of this region in the Alps

simply used rock art to discern the cosmic laws governing the rhythm of the stars, the seasons and meteorological phenomena.

|

|

|

BIBLIOGRAPHIE SOMMAIRE |