|

|

MONGOLIAN "STAG STONES"

The cosmology of the pasforalists, hunters and warriors of the steppes in the First Millennium BC Dr. Jérôme MAGAIL |

|

|

|

There are relatively few traces of these illiterate nomads, hunters and warriors whose territory was bigger than the area of present-day Mongolia. In order to better understand the origin of their habits, customs and cosmology, а part of the research carried out by the French Mission relates to remains from before this period. The tribes, confederated in the second half of the First Millennium BC to constitute а vast nomad empire, have left behind superb rock art compositions. These are the funerary steles known as "Stag Stone" (Fig. 2). At Gol Моd, in а cemetery dating before the Xiongnu necropolis there are still five steles of this type to be seen. |

|

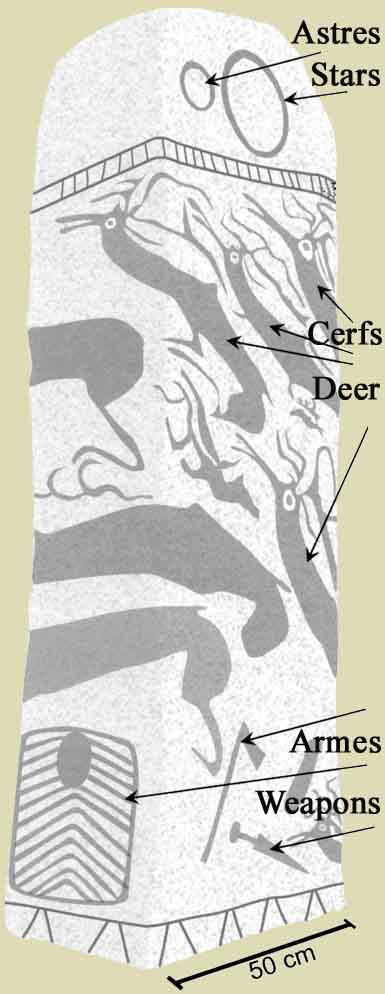

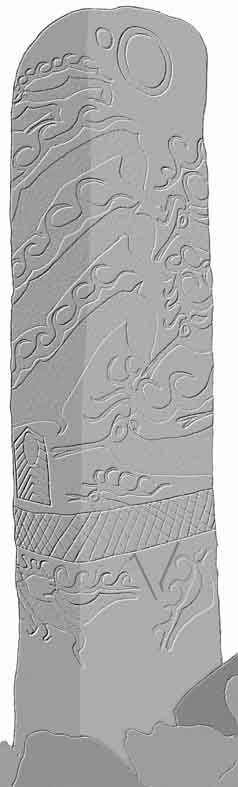

Fig. 2 : Stéle 1 at Gol Mod. |

These monoliths, some as high as 3 m, have various iconic themes

whose style is identical to that from Eastern Mongolia to the Altai, from the Gobi to the Transbaikal. From the

end of the 2nd Millennium to the 3rd Century BC, the artists systematically spread out the figures in the same way

from the bottom to the top of each stele. The Gol Моd Stele 1 (Fig. 3) illustrates this spread perfectly:

|

|

|

А fourth sector, the part of the monolith buried in the earth, certainly relates to the subterranean world, the world of the dead person. On Gol Моd Stele 1, а geometric motif, engraved at the foot of the monument, evokes the separation between the terrestrial and underworld realms. The iconographic themes are often separated by а geometric motif to clearly mark the different areas of the Universe: on Gol Моd Stele 4, а stag is crossing one of these fringes separating the lower part from that of the arms, represented by а shield (Fig. 4). |

The presence of small cervids, at the base of the monument, underlines their psychic role; herds of deer plunging into the world of the dead and surging up from the sepulchral space to rejoin the celestial regions. Their bodies have been deliberately elongated to make clear their movements between the two cosmological extremes. Their silhouette, marked by the rounded form of their antlers and their legs folded under the stomach, is also found in the mobiliary art of the Steppe. Moulded, sculpted and engraved cervids, from the Caucasus to Eastern Mongolia, show very close stylistic particularities. Numerous metal deer (Fig. 5) deposited in Southern Siberian graves close to Minusinsk have similar forms (see map). The cosmology of the art of the "Stag Stones" existed in several iconographic and ritual forms in the Steppe populations of the First millennium BC. Certain horned animals seem to have played a mediating role, enabling the spirits of the dead to pass into the supernatural world beyond our own. In Eastern Kazakhstan (Altai), the team from the Central Asian French Archaeological Mission discovered that this passage to the next world could be shown by other stratagems. In the 3rd Century BC a Saka prince was buried with 13 horses with false horns fixed to their foreheads. In this princely kourgan at the site of Berel' (see map), the sacrificed horses were fitted with pairs of wooden horns imitating those of ibex. This idea was adopted in several places, particularly at Pazyryk whose remains in gold coated wood are preserved at the Hermitage of St Petersburg. The horse seemed to have become the domesticated "ferryman" that had to be made-up fo be reintegrated into the original bestiary. The important place of the stag in Steppe religious representations is linked to its status as a wild animal animated by natural spirits. Its annual movements, the loss and growth of the antlers with the seasons related back to cosmic movements. Its hunting was not just a predatory activity but also an opportunity to distinguish the best warriors and to incorporate the tracking of the animal into a sacrificial rite. This type of practice very likely lasted through from prehistory to antiquity. Numerous hunting scenes were engraved, particularly in the Bronze Age in Western Mongolia, where can still be seen archers aiming at animals sometimes surrounded by dogs. Ancient Chinese texts (Shiji, 110: 2888) state that the Xiongnu used collective hunts to train for war. |

Fig. 4 : Stèle 4 at Gol Mod. |

|

What seems to be a hunting scene was discovered on a rock 6 km west of Gol Mod. Three cervids seem to be being chased by a horseman (Fig. 6). In a style very different from the "Stag Stones"; the stag, the deer and the faun and their pursuer are very badly effaced. These engravings, seemingly from the Earl y Bronze Age, will be studied in more detail during Summer 2004.

|

|

|

The "Stag Stones" also enable an understanding of the significance of the animals represented on the belt buckles and weapons of Central Asian nomads (Fig. 7). This bestiary that was worn, sometimes even tattooed (Pazyryk), certainly had a propitiatory role helping men to be better warriors. The force and spirit of the animal were captured and diffused by the object showing it. The animal fights frequently moulded on swords and belt buckles demonstrated the vigour necessary in inter-tribal combats. Under the funerary "Stag Stones" decorated with daggers, axes and shields rested a warrior buried with his own arms (Fig. 8). At Gol Mod, a dagger and a bow were engraved on the side of one of the steles (Fig. 9). The arms are always shown in a very schematic way compared with the stags. |

|

Linked to warfare, weapons were also part of the attributes of heads of families and clans who wore them both for display and prestige.

|

|

|

|

Certain of them perhaps had the rote of canalising supernatural powers likely to intercede in the favour of their possessors. The Tagar civilization produced superb halbards, the base of whose blades had an animal statuette carved from the block. Such arms, whose fragility precluded their use in battle, were probably carried in rituals and ceremonies. |

|

Among the Xiongnu, the vaunting of the warrior life reached its apogee. At the summit of their social hierarchy, power was not transmitted in a hereditary fashion as with the Han Chinese: The Steppe Emperor (the chanyu) was elected among the best warriors. This conferred on him the title of "Son of Heaven and Earth" and he became the incarnation of the Sun and the Moon before whom he prostrated himself each morning and evening (Shiji, 110: 2892-2899).

|

|

|

A metal sun and moon (Fig. 10) have been found by the French Archaeological Mission in Mongolia in a

Xiongnu tomb at Egiin Gol (see map). These iron pieces decorated the coffin and enabled the dead man's spirit to pass to the

next world. Several centuries before, the "Stag Stones"; whose summits were engraved with two circles, already showed the

relationship between the warrior and the stars (Fig. 11). The passing of the spirit was tightly bound to the position of the

monolith and to its iconography. If the body of the nomad was now sedentary, the funerary art had to perpetuate the journey of

his soul. Before the great Scythian and Xiongnu empires, the "Stag Stones" represented a very codified art that required a sophisticated technical and artistic apprenticeship. The style, the iconographic themes and their distribution show such similarity from one stele to another that the artists must have strictly observed the same rules, leaving little place to personal creativity. In the pluriethnic context of the First millennium, these rock groupings suggest an astonishing cultural coherence over such a vast territory.

|

| Contactez l'auteur - Dr. Jérôme MAGAIL - SITE EN EVOLUTION |